Tribe Celebrates Constitution’s 50th Anniversary

“We, a group of Kenaitze Indians residing principally within the Kenai Peninsula Borough; in the State of Alaska, having a common bond of association and interests, in order to promote our security and social welfare, and advance and protect our common interest as the descendants of the aboriginal Indians within the Kenai Peninsula, do establish this constitution by authority of the Act of June 18, 1934, (48 Stat. 984) as amended by the Act of May 1, 1936, (49 Stat. 1250).”

– Preamble to the original Constitution of the Kenaitze Indian Tribe

With those words as its original preamble, the Constitution of the Kenaitze Indian Tribe was adopted on Aug. 1, 1971.

Adeline Chaffin, who as a member of the Election Board signed the Certificate of Adoption, said it is important to have the Tribe’s rights and by-laws written down.

“That’s the only way it was going to work. You can’t start something and not have a constitution,” Chaffin said in a recent interview. “The constitution tells you your rights.”

Three other signatures appear on the Certificate of Adoption: Election Board Chair Rika Murphy; Election Board Member Alida Bayes; and Roy Peratrovich, then the Regional Superintendent for the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The document was officially adopted by the Tribe, with a vote of 79 in favor and zero against. The Tribe’s Constitution laid out the rules governing Tribal Membership, duties of the Tribal Council, the Tribe’s powers and authority, and rules for Tribal elections.

It was the second vote on the Constitution taken by what was to become the Sovereign Nation of the Kenaitze. The Constitution and By-laws were ratified by a vote of 113 in favor and seven against on Feb. 25, 1971, with the Certificate of Adoption signed by Emil Dolchok. The Constitution was sent to the Secretary of the Interior for approval, which came from Assistant Secretary of the Interior Harrison Loesch on June 21, 1971.

Adoption of the Constitution – and the federal government recognition that came with it – was the result of a long process, with many people contributing, Chaffin said.

“They worked and worked,” said Evelyn Boulette, whose uncle, George Miller Jr., was involved with the effort. “It was very interesting and exciting to get tribal status. It was a new thing. We were just a bunch of people living in Kenai, but we knew we were Indians. It gave us something where we all belonged. … It was our right to have tribal status. It gave us a name.”

The Kenaitze Indian Tribe was first organized as a political entity in 1962, with Murphy as the first recognized chief. Hazel Felton, Murphy’s daughter, described her mother as “a gentle soul,” and said “she was one of the movers and shakers.”

Tribal Members pick salmon from the Tribe’s net at Waterfront in 1989, the first year of the Educational Fishery.

Other “movers and shakers” included Harry Mann, Dolchok, Mary Nissen, Pauline March and Alexander Wilson. Many of the contributions to organize the Tribe were made by women.

When the Tribe first organized, Alaska had only been a state for three years. Among the biggest concerns for those involved in organizing the Tribe were hunting and fishing rights for Alaska Native people. The Alaska Statehood Act authorized the state to select more than 100 million acres of “vacant, unappropriated, unreserved” land, and included provisions to recognize land rights “which may be held by any Indians, Eskimos, or Aleuts.”

The state began making its land selections, often in traditional hunting and fishing areas and before many Alaska Native land claims had been settled. Throughout the 1960s, Alaska Native communities began to organize to better advocate for the rights of Alaska Native people.

Boulette said that fishing and hunting rights drove the effort to organize as a tribe and to seek federal recognition.

“That was our lifestyle,” Boulette said.

Linda Ross, whose father was Harry Mann, has many happy memories of growing up living that lifestyle. She grew up in a house overlooking the Kenai River.

“The bluff wasn’t like it is today – you could run up and down. We would walk on the beach, and get hooligan just below the house,” Ross said. “… My dad hunted every year. We always had moose meat, and king salmon every year.”

Ross and her four sisters, Harriet Seibert, Patricia Mann, Eleanor Wood and Bernice Crandall, helped their father with the family’s fishing site. He had a tractor to help with the nets, and she said he taught her how to drive it when she was just 10 or 11 years old.

“It was wonderful living on the beach all summer,” Ross said.

Chaffin said there was a sense of common purpose among those working on the Constitution and federal recognition. Land rights and hunting and fishing rights were a big part of the conversation, but so was what it meant to be a Tribe, and what the Tribe should meet about.

“We would talk about what the people needed,” Chaffin said.

The Constitution process included several years of correspondence between the Tribe and the federal government. Boulette remembers her uncle going to Washington, D.C., to advocate for tribal status.

Pauline and Clarence March prepare for a moose hunt. Fishing and hunting rights helped drive the effort to organize as a tribe.

Boulette said she’s not sure if those who helped win tribal status realized the far-reaching effects it might have.

“I don’t know if they were thinking ahead … but as they were working on it, they could see how it would benefit the people,” Boulette said. “It was interesting to me to listen to my uncle, and the pride they had in getting it, that this would be a Tribe for our people. They were working for something for everyone, all of us here in Kenai.”

Tribal Elder Clare Swan returned to Kenai in 1973. She said that at the time, even though the Constitution had been adopted, there was still a great deal of work to do. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, passed in 1975, gave tribes the authority to contract with the federal government to operate programs to serve tribal members – but the Kenaitze Indian Tribe had yet to establish any programs.

Swan recalls having to go to Anchorage for things like health care. Other organizations were receiving funds to provide services for Kenaitze Tribal Members. On one of those trips with her sister, Rita Smagge, they decided it was time for the Tribe to provide services of its own.

“We were a tribe just bumping along – we had to go to Anchorage for everything,” Swan said. “My sister said one day, ‘Why don’t we contract for this?’”

Swan said there was a steep learning curve, but that it was the right thing to do.

“That’s the best time to do something – when you don’t know how to do it, but you know it has to be done,” Swan said.

The Tribe’s first health clinic was opened in the late 1970s in space on the former Wildwood Air Force Station, which had been transferred to the Kenai Natives Association in the early 1970s.

Another important development for the Tribe was the establishment of the Tribal Court in 1986. Current Tribal Council Vice Chair Mary Ann Mills helped with the process of establishing the court and writing the court code.

“Our Constitution says that we have jurisdiction over all of our Tribal Members. That’s how we protect them, and we take that very seriously,” Mills said.

Mills said child protection was one of the main reasons to establish a Tribal Court. She said that when children were taken into state custody, it became almost impossible for the Tribe to keep track of them.

The Tribe, with help from Alaska Legal Services, wrote its own statutes. Mills said the Tribal Court is based on the Tribe’s traditional values.

“As long as we follow our values, we do well,” Mills said.

In 2016, the Tribe entered into a partnership with the Alaska Court System to provide a joint-jurisdiction therapeutic court. Mills said the Tribe’s traditional values have served participants in the Henu Community Wellness Court well, too. The Henu Court serves people who face charges related to substance use. The court focuses on sobriety and healing.

“It is an example of good changes to the judicial system in Alaska,” said Mills, noting that the Henu Court has maintained a zero recidivism rate. “Our traditional values work for not only our people, but for all people”

Today, the Constitution continues to serve as the foundation for self-government. In fact, Chaffin said, the process hasn’t changed in 50 years as the Tribal Council seeks to address the needs of the Tribe.

“It is a good document, and it got us to where we are today,” said Tribal Council Chair Bernadine Atchison. “It created our relationship with the federal government, recognizing us as a sovereign nation.”

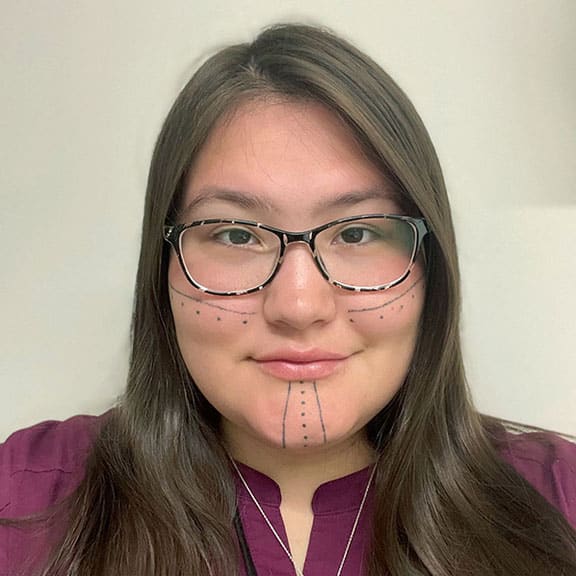

Tribal Council Secretary Liisia Blizzard signs the agreement creating the joint-jurisdiction Henu Community Wellness Court in 2016 with Kenaitze Chief Judge Kim Sweet, Kenai Superior Court Judge Anna Moran, Alaska Attorney General Jahna Lindemuth and Alaska Court System Deputy Director Doug Wooliver. The court, founded on Kenaitze values, is one of just a few joint-jurisdiction courts in the country.

The Constitution has been amended twice, in 1997 and 2019.

The changes adopted on June 16, 1997, made any lineal descendant of a base enrollee “who has a common bond or close association with the Kenaitze Indian Tribe” eligible for Tribal Membership. The amendment removed the requirement that they “be of at least one-quarter Kenaitze Indian blood.”

Amendments adopted on Feb. 28, 2019, removed the requirement that the Secretary of the Interior approve future changes to the Constitution. The changes provide for the Tribal Council or Tribal Membership to call for a vote to amend the Constitution.

Atchison, whose grandmother was Rika Murphy, said there could be changes to the Constitution in the future, and that the Tribe’s Constitution Committee is working on ideas to bring to the Tribal Council and to the Tribe’s citizens for approval.

Atchison said changes might include a bill of rights that focuses on individual rights of Tribal Members, and expanding the Tribal Council from seven to nine members.

She would also like to see the document include more of the Dena’ina language.

The Constitution will evolve as changes are needed for the Tribe to fulfill its mission, “to assure Kahtnuht’ana Dena’ina thrive forever.”

Tribal Elder Coby Wilson was on the Kenai Natives Association Board of Directors at the time that the Tribe adopted the Constitution. He said he’s amazed at the progress the Tribe has made over the past 50 years, and appreciates the work that made what’s happening now possible.

“I’m really amazed, just in the last couple of years, you look at the clinic and how it’s grown,” Wilson said, referring to the Dena’ina Wellness Center, which opened in 2014.

Federal recognition gives the Tribe the ability to negotiate with the Indian Health Service. The Tribe is able to manage the services it provides to best meet the needs of Tribal Members and the community.

From its start at Wildwood, the Tribe’s health clinic eventually moved into Kenai, where medical and dental services were provided in a small office building.

The Dena’ina Wellness Center and surrounding Kahtnuht’ana Qayeh (Village) continue to grow to meet the Tribe’s needs.

In 2011, the Tribe entered into a joint venture agreement with the Indian Health Service to build the Dena’ina Wellness Center in Old Town Kenai.

Diana Zirul, Tribal Council Treasurer and Kahtnuht’ana Dena’ina Health Board Chair, noted that the success of the compact with the federal government not only made medical and dental services available locally, but provided for behavioral health, optometry and wellness services such as the gym for Tribal Members.

Atchison said the ability to form partnerships has opened many doors for the Tribe.

The Tribe is also able to compact with local, state and federal governments to deliver programs and services for Alaska Native and American Indian people. The Tribe’s Constitution authorizes the Tribal Council “to consult, negotiate, or contract with federal, state, and/or local governments and others on behalf of the Tribe.”

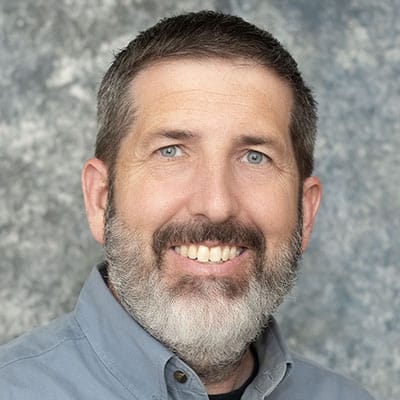

Sonya Ivanoff and Joel Isaak, Language Institute Coordinator, work together on a Dena’ina language story in 2020. An education campus, now under construction, will soon support the Tribe’s expanding cultural curriculum.

“When we were recognized as a Tribe, it opened up doors. Now it’s up to us to recognize those doors are there,” Atchison said. “If you can keep moving forward and developing partnerships, then you’re able to expand and reach more people.”

Atchison cited relationships with Chugach National Forest and the Kenai Peninsula Borough School District that have helped the Tribe with its Susten archaeology program. The Tribe also has had a seat at the table as a stakeholder for planning of the Sterling Highway Cooper Landing Bypass project, which led to funding for an archaeologist and cultural observers.

“If we have good relationships, we can find ways to get the resources we need,” Atchison said.

Other Tribal services benefitting from the Tribe’s relationship with the federal government include Transportation, which was launched with a Federal Transit Administration grant in 2015 and has grown to include a fleet of more than 40 vehicles.

Construction on the new Kahtnuht’ana Duhdeldiht Campus is scheduled to be complete in March 2022, and is funded in large part with federal grants.

“I’m really excited about us getting into that building, and helping our kids learn and grow,” said Ross, who had a tour recently as a member of the Tribe’s Education committee. “I’m hoping that we will be able to be involved as Elders and as Tribal people, for them to know more about their heritage and what it’s like to be a Tribal Member. Those are things that are meaningful to me.”

Atchison said that with federal recognition in the early 1970s came the realization that steps needed to be taken to preserve Dena’ina language and culture. Vera Tschoepel, Frances Lindgren and Charlotte Korpinen formed Dena’ina Quenegha’ne Queedatl’, the Dena’ina Language Society. They worked with Kenaitze Tribal Members Peter Kalifornsky, Bertha Monfor, Fedosia Sacaloff, and others to preserve the language. Meetings took place in people’s homes.

“Now here we are, building our own school and getting ready to hire a Dena’ina language director,” Atchison said. “We’ve come a long way, teaching our language in college and, pretty soon, teaching in our own education campus.”

Boulette said she hopes to see the next generation of Tribal Members continue the work to move the Tribe forward.

“The thing I hope for is to bring younger people into things in the Tribe,” Boulette said. “Younger people need to be involved. The future of the Tribe is theirs. The older people set the stage – they have to carry on.”