After four decades of drug use, a tribal member discovers sobriety

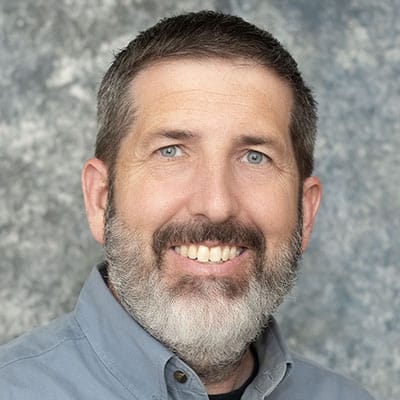

Eli Darien shows his dog Violet some love during a walk near their home in north Kenai. Violet has been a close companion to Darien during both good times and bad.

Blood was seeping into the man’s brain and he was high on cocaine.

The white powder, which he had snorted, was deep in his system when the aneurysm ruptured.

He heard the pop, felt the pop, an excruciating pain.

But he could not go to the doctor. Not with drugs in his system. Not if it meant jail time.

So he waited, aching.

Three days later, bedridden and crying in a dark room, the man confided in his wife.

“I need to see a doctor,” he said.

Then he stood up, felt the world tilt, collapsed and vomited.

He was rushed to the Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage and almost immediately flown to a Seattle hospital, where he slipped into a coma.

Today, two decades later, Eli Darien is 55 years old and enrolled in the Henu’ Community Wellness Court. The court, which opened about a year ago in Kenai, is operated in partnership between the Kenaitze Indian Tribe and Alaska Court System.

Henu’ serves people who face legal trouble stemming from substance use, taking a restorative approach toward healing. It serves people who struggle with drugs and alcohol, who want sobriety, but who are shackled by addiction.

With the nation facing an opioid epidemic, and countless communities searching for solutions, this is the story of one man’s revival and his tribe’s effort to save him.

A lifetime of drugs

During a Henu’ Community Wellness Court session, Eli Darien laughs with fellow participants Shawna Taylor, left, and Ty Hawkins, right, after Darien’s musical Christmas sweater interrupted a conversation.

Darien grew up in Old Town Kenai on the same land that today houses the Dena’ina Wellness Center.

He began using drugs at the age of 14. First it was marijuana, then speed, and others.

By adulthood, although he worked a union job as a tile layer, Darien was trying every drug put in front of him.

“There isn’t a drug I’ve tried I didn’t like,” he said. “I liked it all.”

Legal, financial and health troubles followed.

Court records show misdemeanor convictions for an array of crimes – property damage, drunken on premises, driving without a license – in the mid-1980s and early 90s. Then came formal evictions from his residences in the late-90s.

The brain aneurysm occurred in 1997, when Darien was in his mid-30s, a near-death experience he attributes to cocaine use. He suffered a stroke and was in a coma for nearly a month due to the aneurysm, which leaked blood onto his brain.

Doctors snipped two aneurysms during an operation but left behind a third because touching it would cause permanent brain damage.

Darien’s care team said he defied odds by surviving. Darien said the pain was so intense, he wasn’t sure he even wanted to survive.

“I never thought I wanted to burn to death until that happened,” he said.

Soon after returning home, despite the health scare, Darien returned to drugs.

And in 2002, his wife Beth died at the age of 43. The loss triggered a downward spiral.

Darien remembers little from the two years that followed – “I was high the whole time” – and his legal issues mounted. Reckless endangerment, assault, failure to appear in court, violating conditions of release – an endless circle of drugs and jail, court records show.

But even worse was the pain Darien’s addiction inflicted on his loved ones.

Shortly after Beth died, Darien remembers his stepdaughter coming to his home to help clean. A bundle of syringes fell from his shirt as she tried to fold it. She told him she would not return, or allow her children to visit, unless he got clean.

He didn’t.

The spiral intensified when Darien met a new woman after Beth’s death. At first it was a good relationship – he thought she was the one, he said – but it deteriorated.

Together they did more drugs than Darien had his entire life. She was an alcoholic, he said, and they shared methamphetamine and heroin.

And even when they discussed quitting, Darien did not want to give up meth.

“I told her, are you out of your mind?” he said. “I finally found a dope I’d sell my soul for and you want me to quit now? No way.”

The situation worsened over the years. Darien’s teeth began to fall out. Relationships with loved ones eroded.

The he was charged with possession of a controlled substance in 2012 and again in 2014, Class C felonies, according to court records. There were other charges, too, including assault and theft.

In 2016, in the throw of addiction and a heap of legal troubles, Darien suffered a heart attack.

That same year, Darien remembers a night when the temperature dropped to nearly 30-below zero on the Kenai Peninsula. Living alone in a camper with walls less than 2 inches thick, he ran out of propane. The temperature dropped inside the camper, and he had nowhere to go. A Coast Guard-approved survival suit, what a commercial fisherman would strap on when a vessel sinks, saved his life.

“I put that on and went to bed. Prayed for the best,” Darien said. “Luckily I woke up the next morning.”

A community problem

During the grand-opening celebration for the Henu’ court last year, the tribe’s Chief Judge, Kim Sweet, shared the Dena’ina story of “Nant’ina,” an evil figure who creeps into villages under the cover of fog and inflicts evil and pain on those in its path.

Today, Sweet said, Nant’ina, is in the community in the form of drugs and alcohol.

“The appearance of our land has changed – roads, malls, asphalt and concrete,” Sweet said. “Nant’ina has changed too. No longer an outcast, he is found in our homes, the places we go for companionship, our family gatherings.”

The numbers tell a difficult story, in Alaska and beyond.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, nationwide opioid overdose rates more than doubled among youth ages 15 to 19 between 1999 and 2007. After a decline, the numbers again spiked in 2015. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a 283 percent increase in opioid overdoses between 2001 and 2013. And the 2016 Alaska Statewide Drug Report showed increases in treatment admissions, arrests and drug seizures relating to opioids across the state.

Darien, entrenched for a lifetime, appreciates the problem as well as anyone.

“It’s huge,” he said. “People get out of jail, it’s a never-ending circle. It’s really hard unless you’re ready to say goodbye to those people who are stoned.”

Carol McMormick, a probation officer with Henu’, said one of the key issues is a lack of resources.

Most addicts, she said, simply do not have access to the support they need to get and stay clean.

“People who have been active in addiction for several years, they go to jail and get sober and come out, and they are not only struggling with sobriety but everything else.”

Henu’ aims to break that cycle.

A different court model

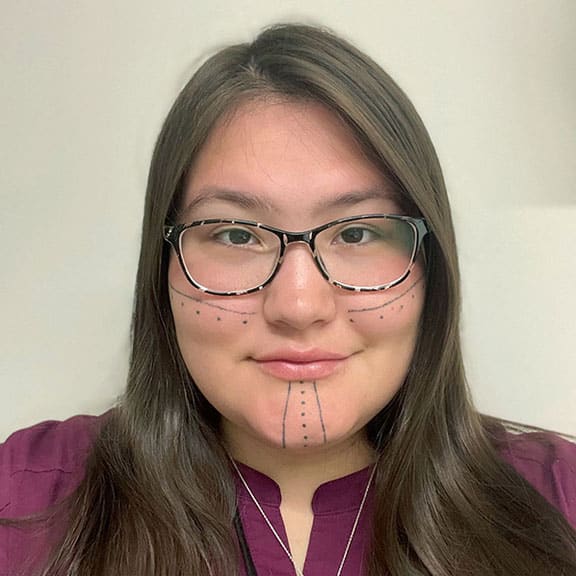

Kenai Superior Court Judge Anna Moran and Kenaitze Tribal Court Judge Rusty Swan, both seated at right, meet with Darien, at left, and other participants during a Henu’ Community Wellness Court session in the Kenaitze courtroom. Unlike the state court, where judges sit above and separate, Henu’ judges sit with participants.

Henu’ is modeled on joint-jurisdiction courts in California and Minnesota that have reported success since opening.

Two judges sit beside each other during cases. One judge represents the tribe. The other represents the state.

It is a post-plea, pre-sentencing court, meaning offenders plead guilty to charges but receive delayed sentencing while they are enrolled in the program. Those who graduate receive favorable outcomes.

The court consists of four phases – orientation and assessment, education and planning, skill development and feedback, and maintenance and transition. It takes about 18 months to complete. Participants must be at least 18 years old.

Those who enter develop a “Life Change Plan” addressing everything from their criminal influences, to their values and beliefs, to their personality, to their family, and more.

They also receive behavioral health counseling, transportation assistance and access to other resources to help them get reestablished in the community.

“Instead of punitive, it’s restorative,” Sweet said.

But the court also is rigorous.

Participants are assigned a probation officer. There are random urine analysis tests, home visits, weekly court hearings, and more.

“There are a lot of rules,” Darien said.

Currently, seven people are enrolled. The program capacity is 20.

During court hearings, participants sit beside each other and update the judges on their progress. Judges ask about highlights and challenges, offer encouragement, and discuss expectations for each participant.

Kenai Superior Court Judge Anna Moran, who represents the state, sees the success of participants as a success for the community.

“This is a chance for us to join together and bring wellness to our community,” she said.

Enjoying sobriety

Darien and his dog Violet start a long walk from their home in north Kenai. Darien has been working to repair damage and neglect to the residence that occurred during his years of drug and alcohol abuse.

Darien has been sober since March 8, 2017, his longest stretch of sobriety in four decades.

When he enrolled in Henu’, he said people doubted he could complete the program. He doesn’t blame them.

“Most of the people were telling me this would be really tough because I had screwed up so many times,” Darien said. “Once I decided I was going to quit, it was different this time. It was easy.”

The strict requirements keep him accountable, and peer support gives him hope and motivation.

Darien is in Phase 3 of 4 of the program and is on track to graduate this year. There is much work still to do, but he is enjoying a life free of drugs.

He often eats lunch at the Tyotkas Elder Center, which is walking distance from court. He helped mend nets at the tribal fishery last summer. He attended the tribe’s Elders Christmas party in December, and watched a nephew’s holiday concert at Kenai Central High School. With permission from the court, he hopes to attend a granddaughter’s high school graduation in Oregon this summer.

A cabin Darien started building years ago but never finished is beginning to take shape, beginning to feel like home. And for the first time in a long time, he is building healthy relationships.

“The clean friends I’ve got, they are just amazing,” he said. “The friends I had while I was using, you always had to watch your back, keep an eye on all your stuff. My friends I’ve got now I’d trust them with my life, with anything I have.”

Darien hopes to one day become a drug and alcohol counselor.

He wants to help others, give back.

“I’m here for a reason,” he said. “I’ve got to be.”