Tribal program helps put former Nikiski High School student on a good path

In the Ts’ilq’u Circle, participants may speak when they are holding the designated talking piece. Some choose the eagle feather, others choose a different item.

It’s about 5:30 p.m. on a Tuesday in March, and Nico Castro finally has a chance to relax.

Life is busy for this 18-year-old living in Anchorage. When he isn’t working at the mechanic shop – like he did this day, from 7 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. – you can find him on campus at the University of Alaska-Anchorage, where he is enrolled in automotive technology courses and pursuing a degree.

These days, life is good for Castro.

These days, life is different for Castro.

“I’ve totally changed my life and my view on life and my attitude in general,” said Castro, who attended Nikiski High School. “I find myself focused on my job and my future and my goals.”

Castro attributes the turnaround to his experience participating in the tribe’s Ts’iłq’u Circle, which means, “coming together as one.” The Circle is administered at the Tribal Courthouse in Old Town Kenai and serves different purposes, but most simply is a place where people come to have important or difficult discussions in a good way. The tribe has operated the program since the mid-2000s.

Many Circle participants are teenagers, like Castro, who are referred from the Alaska Division of Juvenile Justice or the state court system. In these cases, it’s a diversion program for youth who have pleaded guilty or no contest to a first offense and received a suspended sentence pending completion of the Circle. But the Circle is more than that.

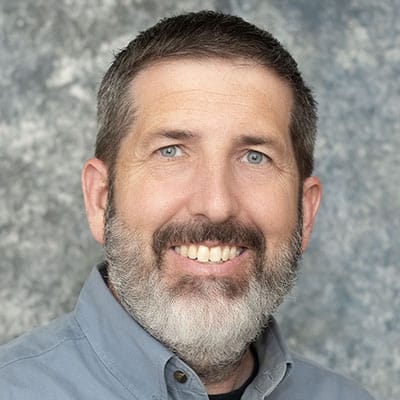

Curt Shuey, who has coordinated the program for about a decade, said it’s open to families, coworkers or anyone facing tough circumstances. The Circle is a place for those who need to talk and make important choices.

“People can come to the Circle for any reason,” Shuey said.

The Circle is predicated on unity and has guidelines designed to foster trust, honesty and respect. A talking piece is passed around to ensure each participant can speak freely and without interruption. Participants sit in chairs, without a table or other obstructions between them.

When someone facing legal consequences comes to the Circle, they bring with them people who are important in their lives – parents, siblings, friends, coaches. The group works together to create a plan for the subject to make amends for the offense.

Each member of the Circle – including the person facing trouble – has an equal say in the plan. The plan is not finalized until every participant agrees. The plan is then put into action and the Circle periodically reconvenes to gauge progress, make adjustments and assure the plan is ultimately completed.

“It’s an approach toward justice where people take responsibility for themselves and they have some input into what they think should happen to make things right and get on a good path,” Shuey said. “It’s not punishment-focused. It’s a different mindset and approach to the court system.”

Castro came to the Circle in high school after he was caught consuming alcohol and a judge gave him the choice of going to youth court or the Circle.

He participated with his mother, a neighbor and Shuey. The group devised a plan that required Castro to speak to a younger person about his mistakes, the idea being for the youngster to learn from Castro’s story and have a chance, simply, to talk. The plan also called for Castro to regularly attend church.

What resonated most, Castro said, was that everyone in the Circle genuinely seemed to care about the outcome. They spoke meaningfully, fairly and from the heart.

“I learned there are lot more people out there who care about me than I thought there was,” he said.

Castro also said it meant a lot to have a say in the outcome, which was a surprise.

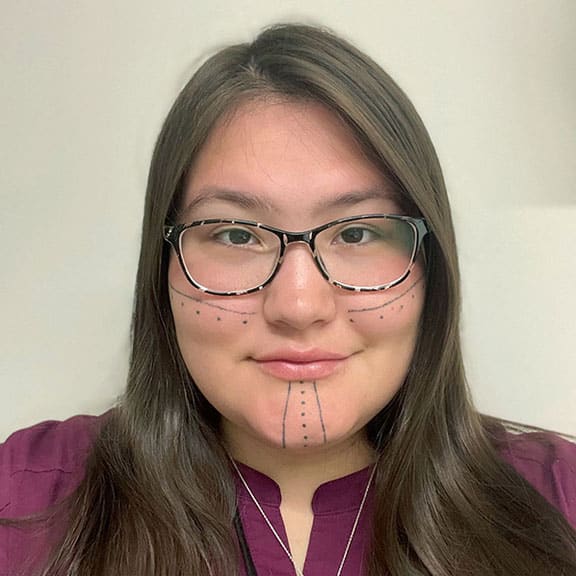

Martina Georges, Circle co-coordinator, said the collaborative approach is one of the most powerful aspects of the Circle, especially for young people accustomed to being told what to do.

“They are thinking they are going to get in trouble and they are going to be sentenced,” Georges said. “But the more the Circle goes on, you can just see their body start to relax. They are starting to think, ‘Oh, wait a second, they are not telling me what I should do. I’m being included to find a solution.’”

For Castro, the experience changed his attitude not just about discipline but life in general. Before the Circle, he said he used alcohol to cope and had little enthusiasm for life.

But these days, life is different for Castro.

These days, life is good for Castro.

“My big emphasis on it is I had a lot more motivation to do something with my life after that Circle,” he said. “It just helped me out a lot.”

CIRCLE GUIDELINES

- Honor the talking piece

- When the talking piece is passed around, only the one holding it should speak

- Speak from the heart – Speak the important things that need to be heard, with honesty, courage and humility

- Speak in a good way

- Choose your words with care for others. Do not attack or manipulate. Be brief and leave time for others.

- Listen in a good way

- Listen to learn, to understand. Give respectful, interested attention. See things through the speaker’s eyes, even if you disagree.

- Remain in the Circle

- Commit to the Circle until everyone agrees to stop, even if it becomes tense or difficult. Play your part.

- What is said in the Circle, stays in the Circle

- Be trustworthy. The stories and words of others are not to be shared in gossip or backbiting.